“Beauty will save the world.” This famous phrase, often attributed to Fyodor Dostoevsky, actually comes to us as a second-hand report from a secondary character in his jangly novel, The Idiot. Though not perfectly crafted, the still point around which this tilt-a-whirl novel turns is his most enigmatic character and the supposed author of this audacious claim, Prince Myshkin. The Prince, described by Dostoevsky as a “positively beautiful man,” moves like the “bright people” in C. S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce, the only solid person in a society of ephemeral shades whose petty jealousies, dark passions, and Main Line-worthy ladder-climbing makes him out to be a singularity, an “idiot.” The young man who reports the phrase, Ippolit, is a consumptive skeptic who sneers at Myshkin and his claim. In a wised-up and broken-down Ippolit world, what place could Beauty possibly have? Perhaps by placing this famous phrase in the second-hand mouth of a first-rate cynic, Dostoevsky pushes it across the page to us as a question: “Will beauty save the world?”

It's a question the novel leaves unanswered.

Pondering this question, we might muse whether embodied beauty is a refraction of the beautiful God himself and could be a conduit through which God draws us to God’s self. Beauty also offers refreshing delight to our sometimes weary cities and souls. When made by embodied images of the beautiful God, it can remind us we were made to be makers, sub-creators whose vocation includes playing with the material world and tacitly affirming its goodness by making more of it than if it were left to itself. And so pigment, oil, and flax become Henry Ossawa Tanner’s The Annunciation, chalk sticks become Mary Cassatt’s Mother and Child, sounds become Bach’s Cello Suite #1, played on instruments made from trees and sheep guts, stone becomes Michelangelo’s Pieta, sand, ash, lime, cobalt, and copper become Chartres Cathedral’s stained-glass windows, the larynx becomes Puccini’s La Bohème, and muscle and tendon become Saint-Léon’s Coppélia.

Because God is beautiful and delights in created beauty, because embodied beauty has been woven throughout the Jewish and Christian traditions, and because participating in beauty seems integral to a well-lived ordinary life, The Templeton Honors College now includes a required course called “Art & Beauty,” our freshmen cohort sings in a two-semester chorale, and The Benoliel Arts & Culture Series sponsors students to Philadelphia’s finest venues. In addition, Templeton Hall has been created as an enclave of ambient beauty, a place with spaces dedicated for beauty like the Clemens Recital Hall and The Merriman Family Art Gallery.

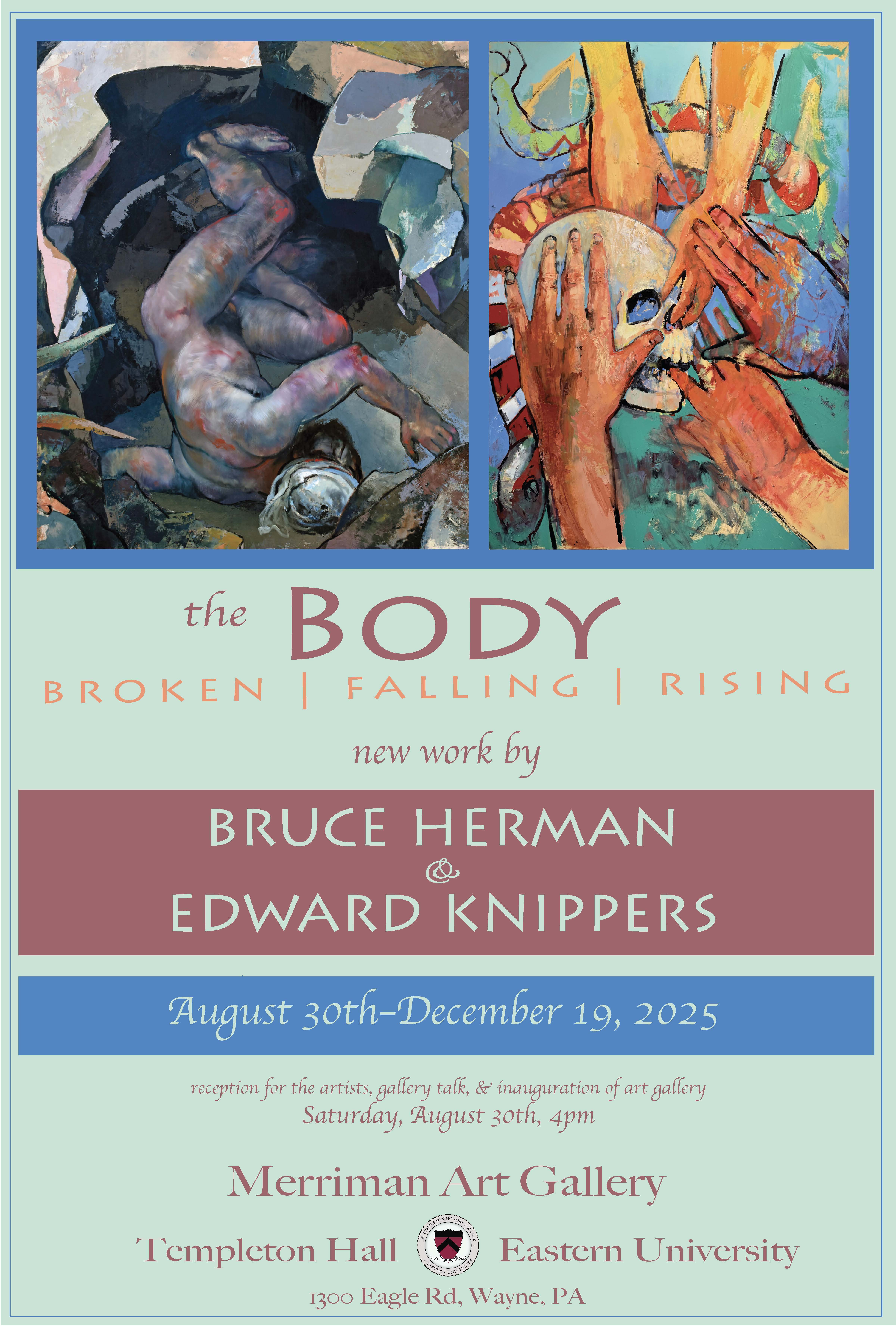

This fall you have several opportunities to bring your body to visit Templeton Hall in person. On August 29 at 10:00 a.m., we will celebrate its completion with a Building Blessing ceremony during which we ask God to “bless this house.” The next day, on August 30, at 4:00 p.m. we will host a reception to officially open The Merriman Art Gallery with a joint show from two of the most significant Christian artists of the last 50 years, Bruce Herman and Ed Knippers. Both artists will speak at the opening and their show, “The Body: Broken | Falling | Rising,” will be on display until December 19. Finally, on November 8, we will enjoy a day-long celebration of Templeton Hall leading up to our 25th Anniversary Gala that evening with poet Malcolm Guite.

Whichever event brings you to Templeton Hall, let me also invite you to peruse the visual art adorning its walls. This art will come from the permanent collection of the Honors College, a collection we have curated to embody Templeton’s theological, philosophical, and literary culture. In our collection are wonderful pieces from Herman and Knippers themselves—including Knippers’ 8’ x 12’ mural, “The Good Samaritan”—but also works from the important French artist Georges Rouault, the Jewish cubist Irving Amen, the Japanese Mingei artist Sadao Watanabe, and the Harlem Renaissance artist, Romare Bearden. Among our Bearden collection are three from his “Black Odyssey” series as well as his important piece, “The Lamp,” commemorating the 30th anniversary of “Brown vs. The Topeka Board of Education.”

Because Dante’s Comedy embodies our Christian literary tradition, you will see the Italian Luigi Pompignoli’s exquisite 19th c. painting of Dante and Beatrice ready to ascend the spheres, two alabaster sculptures of Dante, and an enchanting pre-Raphaelite stained-glass window of Dante, currently being repaired and framed by the local stained-glass master, Andrew Milano. Of Shakespeare, you may turn a corner to find a simple 18th c. portrait of the bard or Eduard Ender’s stunning 19th c. oil, “Shakespeare Reading Macbeth at the Court of Elizabeth I.”

As you wander the building, you might pause in front of Irving Amen’s colorful semi-cubist painting, “The Prophet,” or stop to study “Tetramorph,” a fantastical pen, ink, and marker work commissioned for Templeton Hall from the Russo-Finnish artist Maria Susarenko. Like medieval tetramorphs, it depicts the four gospel writers as Ezekiel’s creatures around the risen lamb. In the Austin Ricketts’ Reading Room, you can sit with old Russian icons and contemporary Ukrainian ones from women associated with the Lviv School of Icon Painting, created and shipped under the current threat of Russian guns. In the Boehlke Library you may discover “Reading the Bible,” an oil from George Henry Story, best known as one of Abraham Lincoln’s portraitists. In another room, a small 18th c. oil on copper of St. Peter accompanies a large Spanish 17th c. oil on wood of St. Paul writing in chains next to an arresting 16th c. Dutch oil on board called “Ecce Homo.”

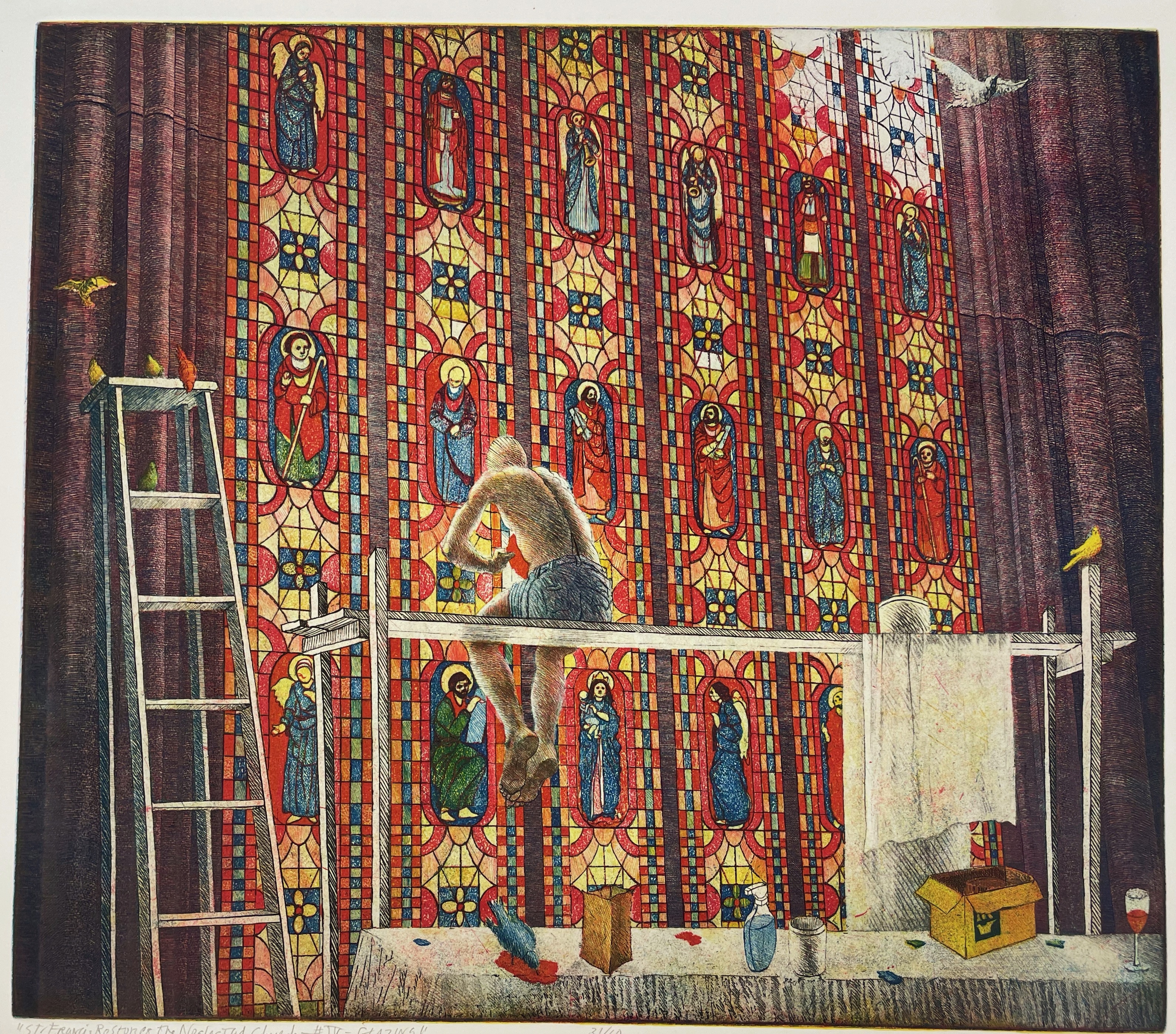

Not least among Templeton’s permanent collection is the complete suite of James Munce’s twelve color and monochrome etchings, “St. Francis Repairs the Broken Church.” This suite is the result of a twenty-year project from a Kansas master. When you see it, recall that each piece required the artist to use a needle, zinc plate, acid, wax, and inks to bring these poignant and playful images to life. And remember that every color in every piece required its own separate printing. Works from this remarkable series will naturally find their home on the walls of the “repaired” Workman Hall, once “broken” but now transformed into Templeton Hall.

These are just a few of the pieces you may encounter while wandering around Templeton Hall in the months and years ahead, along with works from Leonard Baskin, Marc Chagall, Patrick Pye, Steve Prince, Jim Janknegt, Fritz Eichenberg, Barry Moser, and others.

Complementing performances in Clemens Hall and rotating exhibits in the Merriman Gallery, this growing art collection will embody our curriculum, enframe our college culture, and nurture the ambient beauty of our new home. If you are interested in contributing either funds or comparable art to the permanent collection, please get in touch.

Does beauty have a place in a wised-up and broken-down Ippolit world? Will it save the world?

Come and see.